by Bruce Dunlavy

(An index to my other posts is available from the pull-down menus at the top of this page, and my blog home page and index of other posts may be found here.)

Over one-third of working-age Americans have 401(k)-type investments to fund their retirement years. The term “401(k)” applies to only one of the programs whereby workers can defer some of their paycheck each month by having their employer withhold a given amount of money from each paycheck and place it in an account which will allow the withheld money to be saved and/or invested with the payout deferred until retirement. Plans for workers in non-profits are 403(b) accounts, and 457 accounts for government employees. They work the same way, and for the sake of simplicity, “401(k)” is often used to describe them all.

At the beginning of 2025, the total assets of all these accounts was over nine trillion dollars, with over 70 percent of that total invested in stocks. On April 3 and 4, the stock market plunged six percent each day, the largest two-day crash in the history of the bellwether Standard and Poor S&P500 Index. The total value lost was nearly five trillion dollars.

Investors who have been used to overall rising markets watched their holdings decline a significant amount in a frighteningly short time. Many of them are now looking at their diminished accounts and wonder if they should join in the sell-off before they lose more money. Most of those have never experienced this kind of rapid decline. This kind of rapid decline does, of course, happen periodically, but not often enough for most people to get used to seeing it. Mental images of the crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression of the 1930s are flashing through the minds of stockholders.

When a 401(k) investor looks at the bottom line of their account report and sees a big number with a minus sign in front of it showing a big decline in value, how should they react? Nobody likes to see a big chunk of their holdings disappear.

[Full disclosure here: I am a historian, not an economist. I do not intend to recommend here, but to explain. Before you make any investment decisions based on what you read here, do your own research into this issue. Read, study, consult experts. I certainly do not have direct access to The Truth.]

Is this downturn hurting shareholders? American economic wisdom has an answer. That answer, as usual (after all this is economics), is – “that depends.” But what, we may ask, does it depend on?

It depends on your risk tolerance and your comfort with uncertainty, among other things. Mostly, it depends on how close you are to retirement. At retirement, you will stop putting money into your 401(k) account and start taking money out. If you are nearing that point – less than eight or ten years – you would be right to be concerned, especially if you have not invested wisely.

What is wise investing for retirement? In short, follows this general rule: The closer you get to the stop-putting-in-and-start-taking-out stage, the more you should steer towards capital preservation. Capital preservation just means investing in safer kinds of holdings. Fewer volatile equities and more stable securities. One example of this is having less money in stocks and more in bonds.

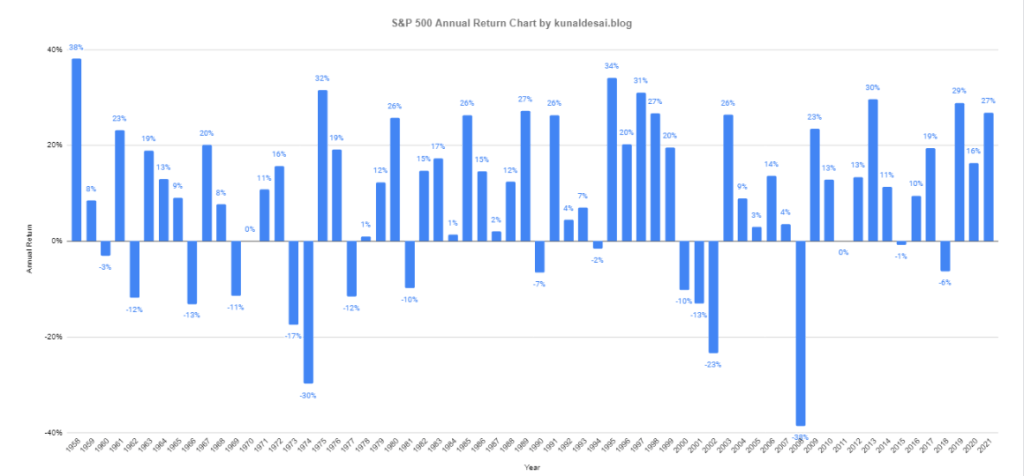

If you are young, with many more work years ahead of you, and you have the stomach to withstand the occasional April 3 and 4, 2025 without getting ulcers, you are probably best off primarily in stocks and stock funds. The aforementioned S&P500 index, a capital-weighted rendering of 500 stocks representing 80 percent of all the money in publicly traded equities, has risen in most years. In my lifetime (since 1950), it has gone up in 58 years and down in 17 years. The up years have ranged from one percent to 43 percent, the down years have registered declines from one percent to 37 percent. The overall value of the index, the increases having vastly outweighed the decreases, has risen from about 230 then to about 5600 today, even after its recent decline.

Image credit: theawakenbuddha.com

If you are a young worker-investor, and you can remain comfortable with the ups and downs of the stock market, your account will likely do better in equities than in some other, safer investments offering a lower return.

What a 401(k) does, by investing a stipulated amount each pay period, is called “dollar-cost averaging.” This method, and its slightly better sibling, “dollar-value averaging” are the most productive ways to invest small, but regular, amounts of money over time. You buy stocks or mutual funds as money comes into your hands.

Now let us reassess what this means for your course of action now. Success in investing is expressed in the old saying, “Buy low, sell high.” Look at what your retirement account does. When you put money into it from each pay period, are you buying or selling? Obviously, you are buying.

If you put the same amount in paycheck after paycheck, you are buying more shares when the price is low, and fewer shares when the price is high. This way, when the price of a share of a stock or a mutual fund goes down, you are buying it at a discount. You are getting more shares for the same amount of money. The opposite happens when the price of a share goes up.

Normally, when the price of what you are buying goes down, you are happy. The same should be true when you are buying an investment in your distant future. If you are not yet 40 years old, you have plenty of time to see your holdings rebound and increase. As you age, you will likely want to put more of your holdings into safer holdings to preserve your gains. But in your younger years, you can probably afford to make investments with more risk but better returns in the long run.