by Bruce Dunlavy (My blog home page and index of other posts may be found here.)

President Donald Trump’s proposed budget calls for an increase in the funding for the space program. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is to be one of the select agencies to get more money than in previous budgets. Included in the package is the development of a manned mission to the planet Mars. Travel to other places in the universe has been an idea that has captured the imagination since the 1800s, and reached fruition in the Twentieth Century.

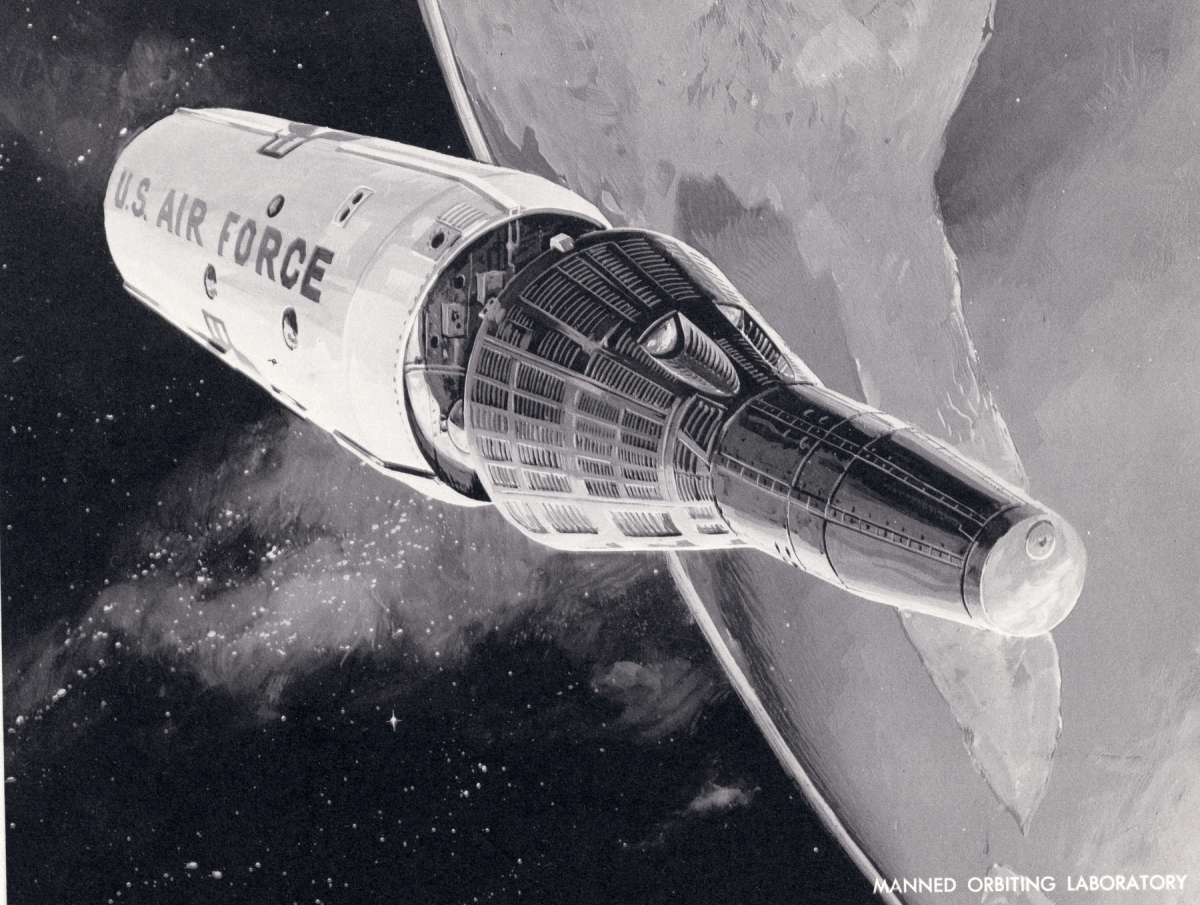

Image credit: leonarddavid.com

In 1966, the inaugural season of the television program Star Trek characterized the mission of space travel as “to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before!” To the show’s fans, that encapsulated the whole point of going into space, but in fact that has never been the goal of space exploration. Indeed, it has never even been a popular idea.

During my youth and adolescence in the 1950s and 1960s, the “space race” was a matter of great importance to Americans, but not for the reasons people think. Not even for the reasons people thought then, for that matter (primarily, “to show the Russians who’s best”). It was actually part and parcel of a bigger issue that was on the minds of everyone at the time.

As World War II closed in 1945, America’s leaders knew that the next conflict had already begun. Our new enemy was Communism, and its prime practitioner was Russia, then known as the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). It was accepted wisdom that the next war would be fought against them, but that the USA could hold the Russians off as long as we had nuclear weapons and they didn’t.

It was not long before the USSR acquired such weaponry, for the knowledge and material for creating it was more widely known than Americans liked to believe. By 1953, the Russians had developed thermonuclear devices (hydrogen bombs), which put them on a level playing field with the USA. Those of us growing up at that time were certain there would be a nuclear war with the USSR. Such a war was not a question of “if,” but of “when.” There would soon be a nuclear war with the Russians, and we were not only going to survive, we were going to win.

The “nuclear triad” of military capability is considered to be the cornerstone of American defense policy. Land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), submarine-carried ICBMs, and bomb-carrying aircraft are the ways the USA armed forces can deliver nuclear warheads anywhere in the world. Whether it is enough to deter or retaliate against a direct attack has, thankfully, never been tested.

In the early 1950s, however, there was another possibility. Both the USA and the USSR were working to develop artificial satellites to place into Earth orbit. It was a natural assumption that the first nation in space would be the first nation with nuclear weapons in space. Having satellite-based nukes meant having weapons that could be fired after Earth-based weapons had been neutralized. Even after missiles had been launched toward the weaponized satellites, they would not get to them until the space-based weapons had been launched by radio signals sent at the speed of light.

As a result, both the USA and the USSR began urgent programs to develop rockets capable of launching satellites into Earth orbit. Beyond that was an even bolder plan, getting to the Moon. The first nation to establish a nuclear weapons launch site on the Moon could potentially rule the world from 240,000 miles away.

The American public, however, was not particularly keen on space exploration. Yes, there has always been a vocal group clamoring for it, but Joe Lunchbucket and Sally Housecoat considered it money wasted on pointy-headed pipe dreams. The government needed a way to increase public interest in the space program.

The key to provoking popular enthusiasm was the introduction of the astronaut program. The engineers developing space plans did not want people on board their spacecraft. In their view, humans are too unreliable, too prone to breakdown, take too long to fix, and are subject to unpredictable fits of emotion, stress response, and independent thinking.

There was much discussion of whether American spacecraft should have humans on board, and the matter gained greater urgency after the USSR launched the first satellite, Sputnik, in October of 1957. The managers of the space program insisted that people would have to fly in space to gain the necessary public interest and support. They overrode the engineers’ contention that those people should be passengers, not pilots, and should merely ride in the space capsule, with no input into the craft’s control. Despite concerns by President Dwight Eisenhower, a career military man, the decision that prevailed called for pilots, and thus the first astronauts were all jet-propulsion test pilots.

In 1958, the “Mercury Seven” were introduced to the public. They were hailed as the flower of American manhood – those who, in the title of Tom Wolfe’s 1979 book, had The Right Stuff. A broad wash of publicity and a guessing-game over who would be the first to ride a rocket into space kept them continually in the public eye, and the USSR’s 1961 launch of the first manned spacecraft turned the eagerness and adulation to a frenzy.

In his inaugural address that January, President John Kennedy had committed the USA to a manned mission to the moon before the decade was out, if for no other reason than to show the USSR that we could do it and, if necessary, point nuclear weapons at them from a safe Moon base. That same year, the two space powers reached agreement on a treaty banning nuclear weapons in space, but the USA went ahead with its lunar mission plans to ensure that the deal had teeth.

The USA did, indeed, send a mission to the Moon by 1969, and several more afterward, but the program ended in December of 1972. It was considered no longer necessary to expend money and effort on further manned exploration, because the nation had proved what it set out to prove – that we could, if necessary, put weapons on the Moon.

The space program faded into the background after that, and no further Moon missions got beyond the pre-proposal stage. At this point, the phrase, “If we can put a man on the Moon, why can’t we……?” has lost its significance, since the USA cannot do it without a substantial revitalization of the manned space program. Even going to the International Space Station now requires Americans to hitch rides on foreign rockets.

Now Mars has been resurrected as the next target. After 45 years, the nation is seriously considering again sending astronauts to other solar-system locations. What has changed to provoke this re-focusing on space activity? Could it be the capability of non-governmental entities launching satellites? Or might it be the possibility of powerful missiles and nuclear weapons in the hands of the unpredictable North Korea?

In any case, the United States is again turning to manned space exploration to fire American ambition and turn the eyes of the people skyward. Perhaps landing on Mars is the actual goal of such a program. More likely, it is a means to another end – increased public support for space activities for another purpose that is much closer to home.