by Bruce Dunlavy

(An index to my other posts is available from the pull-down menus at the top of this page, and my blog home page and index of other posts may be found here.)

As I publish this, it is November 20, 2019, 85 years to the day after a Congressional committee began hearing testimony on one of the most curious – and least-analyzed – events in American history.

The story of the “Business Coup” begins with the inauguration of President Franklin Roosevelt on March 4, 1933. After easily defeating incumbent Herbert Hoover in the election of 1932, Roosevelt took office and immediately began a flurry of activity designed to bring the American economy out of the Great Depression which had begun in 1929 and deepened in subsequent years.

Roosevelt’s initial actions were so rapid and so forceful that the beginning of his term was known as The Hundred Days. The firestorm of legislative proposals and executive actions began with an effort to deal with the fallout from multiple bank failures across the nation, and followed with progressive plans including these:

• Federal Emergency Relief Administration to provide immediate help to the ill-fed and ill-housed;

• Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), putting unemployed men to work on forest and soil conservation efforts;

• Agricultural Adjustment Act, to raise the prices of farm commodities;

• National Industrial Recovery Act, to counter the effects of the deflationary depression;

• Tennessee Valley Authority, to create a series of Federally built and operated dams to produce hydroelectric energy and thus stimulate agricultural output in poor areas of the rural Upper South.

These and other measures Roosevelt undertook – especially a plan to remove the national monetary structure from the gold standard – shook most American bankers and industrialists mightily. They feared inflation would be loosed on the country, threatening their fortunes. They saw an advancing socialism looming over their businesses and their financial holdings, and the likelihood of their gold being redistributed to the undeserving poor.

In those 100 days, a powerful group of these men began to talk among themselves of a sort of coup d’état that could strip Roosevelt of most of his presidential powers and leave him as a figurehead to portray the kindly national paterfamilias who would kiss babies, cut ribbons, and generally present a benevolent visage for military-backed fascist control. The only thing needed was to find someone who had the trust of the military, especially the common soldier, and could rouse them to enforce the coup.

The figures involved in this proposal are shadowy and uncertain, but foremost among them is surely Robert Sterling Clark, an heir to the Singer Sewing Machine fortune. Clark recruited two less-prominent men, middle class bond salesman Gerald C. MacGuire and Bill Doyle, head of the Massachusetts American Legion. It became their job to pitch the idea to a man who would be willing and able to take over the real running of the country.

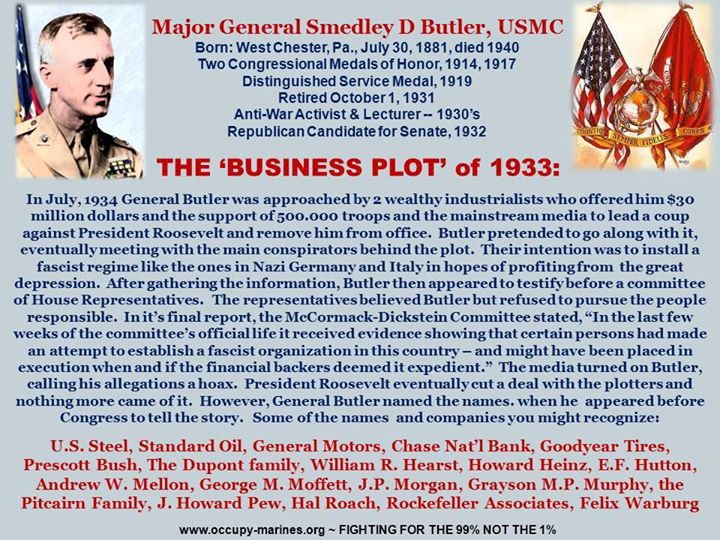

Beginning in mid-1933 and culminating in a proposal on August 22, 1934, the two men pursued retired Major General Smedley D. Butler, former commandant of the Marine Corps. Butler was a widely-respected military man and loaded with honors. He was the highest-ranking member of the Marine Corps and had distinguished himself in combat as one of the few men to be awarded the Medal of Honor twice.

Butler was also revered by American military men for having supported the Bonus Army in 1932, when World War I veterans converged on Washington demanding an early distribution of bonuses they had been promised. Butler made an appearance that rallied the men, but a few days later they were dispersed on orders of President Hoover by cavalry led by General Douglas MacArthur and tanks under the command of then-Major George Patton.

Equally important, Butler had known Clark in the Boxer Rebellion, giving the coup plotters an entry. Clark and MacGuire were certain Butler was the ideal man to become the de facto leader of the United States in the proposed position of Secretary of General Affairs. Butler was to give the orders and the military was to carry them out while FDR was quietly shunted aside.

The plotters told Butler they could raise an army of 500,000 men through American Legion posts and that they had three million dollars (and could get as much as 300 million) from financiers to obtain weaponry produced in Germany through American industrialists. Roosevelt would be sidelined with “health problems” and the country would be Butler’s to run. The plotters expected to find him both amenable and easily manipulated.

The plotters had recruited the wrong man. Butler dropped a dime on them. He put the plotters off temporarily, ostensibly to consider their offer but actually to run his own investigation into what they might be up to. He contacted his former personal secretary, Paul C. French, who was then a reporter working for the Philadelphia Record and the New York Post. Butler asked French to meet with MacGuire and see if he could ferret out how serious the plot might be and how far it could extend.

Around the same time, a Congressional committee (precursor to the notorious House Committee on Un-American Activities) led by Reps. Samuel Dickstein of New York and John McCormack of Massachusetts (who would go on to be Majority Leader and then Speaker of the House) was tipped off and began investigating as part of an inquiry into Nazi connections in America.

The testimony given during the Committee hearings was astounding. The first witness, Capt. Samuel Glazier, testified briefly about Nazi propaganda at a CCC camp. Then Butler recounted in detail the contacts he had had with the representatives of the plotters. The Committee also heard from French, who corroborated Butler’s testimony, and MacGuire, who denied everything.

After three days of testimony, the Committee stopped the hearings. They did not call any other witnesses, and made it clear that they thought it improper to summon anyone whose name had been mentioned in connection with the proposed coup only through hearsay, specifically by MacGuire to Butler. Such names included some of the most prominent men in America – John W. Davis and Al Smith (the 1924 and 1928 Democratic Party candidates for president), bankers such as J. P. Morgan, Andrew Mellon, and the Chase Bank, and industrial giants such as U.S. Steel, Alfred Sloan of General Motors, various members of the DuPont and Harriman families, Goodyear Tire, Remington Arms Company, William Randolph Hearst, Henry Ford, and S. B. Colgate. Prominent among the financiers was one who, Butler was told, would be able to get arms and munitions through suppliers in Nazi Germany. That man was Prescott Bush, later U. S. Senator, father and grandfather of presidents, whose connections to Nazi arms manufacturers have been the subject of considerable commentary.

Image credit: occupy-marines.org

In the end, the Committee’s final report stated, “There is no question that these attempts were discussed, were planned, and might have been placed in execution when and if the financial backers deemed it expedient.”

The transcripts of the testimony mysteriously faded from view and then returned in an altered form. No verified copy of the original transcripts can be produced, but a reasonable rendering – along with some of the changes made afterwards – can be found here.

With the exception of French’s publishers, the Philadelphia Record and New York Post, major newspapers dismissed the whole affair. The New York Times spoke for most when they called it “a gigantic hoax.” Time pooh-poohed the story, as did most magazines. The investigation received modest editorial support from left-leaning journals such as The New Republic and The Nation.

Gerald MacGuire died March 25, 1935, less than three months after the Committee’s final report. He was 37 years old. His death was attributed to pneumonia brought on by weakness from responding to accusations against him.

Whether the Business Coup was imminent or even viable is uncertain, but it is clear that it existed and that, once exposed, it was quickly dismissed as the half-drunken cocktail chatter of some Roosevelt opponents. The evidence and transcripts became hard to find, and even 85 years later, the only book on the subject is the 1973 work The Plot to Seize the White House, by Jules Archer. It is an unprofessional work by a man who was not a professional historian or historical analyst. No historian has published a comprehensive examination of the Business Coup. The most recent scholarly study is a senior honors thesis written by Wesleyan University history major Emily Lacy Marshall in 2008.

Many of the influential political, banking, and industrial businesses and families mentioned in connection with the attempted fascist coup of 1934 are the same ones that are influential in American political and economic circles today.

Draw your own conclusions.